growing up in da u.p.

remembering a 1960s dairy farm childhood

In the 1960s, my mom, Kathy, grew up on a small dairy farm in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula (“da U.P.”) alongside her parents, Ann and Vince Aman, and her three siblings, Bruce, Kay, and Karen. This piece aims to capture what it was like growing up in that time and place, preserving a way of life before it fades from living memory.

Routine

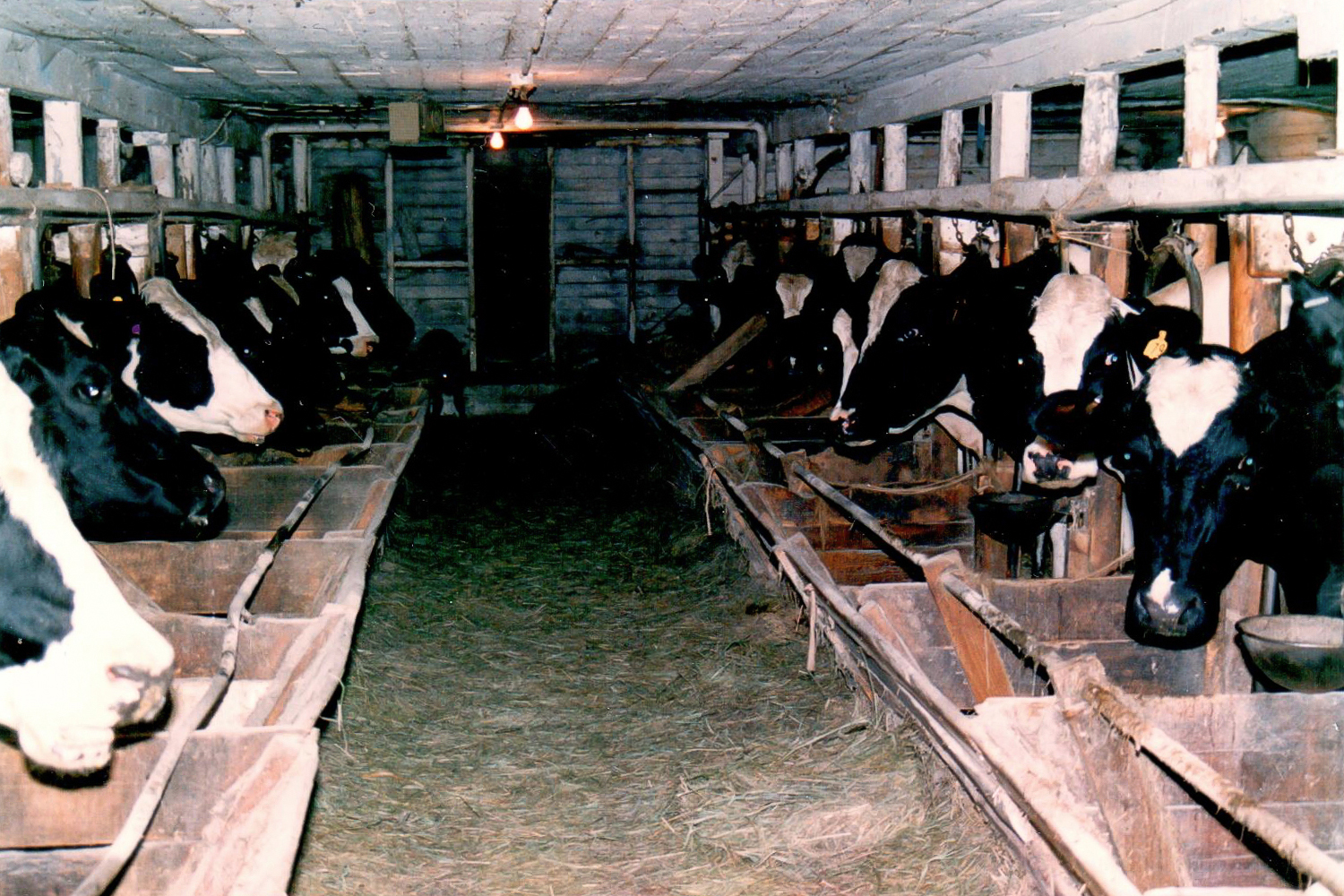

Farm life revolved around milking the cows. They ran on a twelve-hour clock, and everything else—school, supper, sleep—followed that rhythm.

“It was routine,” Bruce says. “Twice a day. Didn’t matter if it was a weekday or a weekend or a holiday.”

Their father, Vince, got up at 4:30 a.m. to feed and milk the cows. He then washed up, changed clothes, and worked eight hours at the Peterson Fence Factory in Carney. After his shift, he came home, ate supper, and went straight back out to the barn for evening milking.

“I don’t know how he did it,” Bruce says. “I really don’t.”

After nightly chores, an exhausted Vince would sit down in his recliner with the newspaper. Most nights he fell asleep before making it to the second page.

Their mother, Ann, kept everything else running. Meals appeared on the table like clockwork. Clothes were washed. The kids and the house stayed clean. Food was canned and frozen for winter. Some afternoons, she watched a soap opera or called a neighbor, but most waking hours were spent keeping the household moving.

Nobody talked much about feelings. Kids rarely questioned the fairness of chores; if they did, Ann would say firmly, “Quit your complaining, or I’ll give you something to complain about.” You were part of the family, and you played your part. That was enough.

Living off the land

The farm provided roughly three-quarters of the family’s food.

Each year, they butchered a steer. During hunting season, the freezer filled with venison—two deer every year, one shot by Vince and one by Bruce. The garden supplied potatoes, carrots, onions, beans, and peas. Blueberries and raspberries were canned and shelved for winter. Apples were peeled and turned into applesauce; Kathy recalls they once canned 65 quarts of applesauce in a single day.

“It’s amazing, thinking back,” Kathy says. “How much we grew ourselves.”

The essentials they didn’t produce themselves came from the store—bread, cereal, and bologna.

Milk was the farm’s main product. Every couple of days, metal milk cans were filled and stored in a concrete bathtub to keep them cool. The milkman, Dean, came by regularly to collect them. On Christmas, it was customary to invite him inside for a shot of whiskey—a tradition shared by nearly every family on his route. By the end of the day, Dean usually had more than a few.

Seasonal changes

Winter meant that cows stayed inside, so the barn was cleaned daily. An apron chain carried manure into the spreader, which had to be emptied immediately—before it froze solid.

“If it froze in the spreader,” Bruce says, “you had big problems.”

In summer, cows grazed outside and came into the barn only for milking. Milk production increased once fresh grass came in, and the barn stayed cleaner longer.

Summer also meant haying. Cutting. Raking. Baling. Everyone had a job—stacking bales, working the elevator, climbing into the haymow. Because the younger kids were less physically able, they often drove the tractor, starting as young as seven years old.

“It was intense,” Kathy says. “Busy days. Everybody was involved.”

At the end of haying season came the reward. Every year, after the last bale was stacked, the family went to Wells Park for a picnic—hamburgers, brats, and a rare afternoon off.

Until that evening, when it was time to milk again.

Daily comforts

At their first farm, the only indoor plumbing was a kitchen sink. There was no toilet or shower.

When nature called, adults went to the outhouse. Younger kids used a bucket kept in the corner of the kitchen.

In warmer months, bathing happened outdoors. A sprinkling can was filled with water in the morning and left in the sun to warm. Later, standing barefoot in the grass, they poured it over themselves, soaped up, and rinsed.

“In the fall, it was cold,” Bruce says. “You didn’t dilly-dally.”

In winter, they washed up at the kitchen sink with a washcloth.

When the family moved farms in the late 1960s, everything changed. The new house had an indoor toilet. And in the basement: a shower.

“I thought, this is awesome,” Bruce remembers. “I think that was the first real shower I ever took.”

Corralling the cows

When a cow went into heat, Vince would tell Ann to “call the bull man.” He arrived the same day, catalogue in hand, flipping through pages that listed different bulls and their traits. Cows were inseminated on the spot, part of the routine business of keeping the herd going.

Not all farm work was predictable. Once, when Kathy was twelve, she was trimming grass beneath an electric fence with a sickle—necessary work, since tall grass could short out the wire. She was careful not to touch the fence.

Suddenly, an aggressive cow came up behind her, pinning her between the animal and the electrified wire. With no way out, Kathy swung the sickle. It lodged squarely between the cow’s eyes, stunning it just long enough for her to duck under the fence and escape.

Vince later removed the sickle, and the cow continued on its way.

Animal friendships

There were outdoor dogs, barn cats, and frequent litters of kittens. Each child had a favorite cow—and every cow had a name. Kathy’s was Sylvia. Bruce’s was Crooked Face.

And then there was Willie.

Willie was a steer—rare in that he was gentle enough to ride. One day, he was simply gone. Kathy searched the woods in tears, calling his name day after day.

“I was devastated,” she says.

Willie had been shipped to market. Their parents never said a word.

Loving animals—and losing them—was part of life.

School

School fit around the farm, not the other way around.

They were the first ones on the bus in the morning and the last ones off in the afternoon. Long rides, early mornings, late returns—all before chores began again.

Extracurriculars were rare. Bruce once asked Ma if he could try out for basketball.

“She said no,” he recalls. “‘You got chores to do.’”

He never asked again.

Teachers, however, understood. Bruce remembers his history teacher letting him sleep in class—not out of indifference, but understanding. Years later, the teacher admitted he knew exactly what was happening.

“I knew your circumstances at home,” he told Bruce. “You had a passing grade, and that was good enough for me.”

One year their bus driver installed an eight-track player—cutting-edge technology at the time. Two tapes played on repeat. It was sensational.

On the last day of school, the bus driver always stopped at a small gas station to buy every kid a soda or candy bar.

“Try that now,” Bruce says. “You might lose your job.”

Play was outside

When there was time to play, it happened outdoors.

They built forts in the woods from scrap lumber their father brought home from work. Bruce even built roads back there—waiting for the county road commission to fill potholes, then quickly scooping up leftover blacktop with his Radio Flyer wagon and hauling it into the woods.

“I never got caught,” he says.

There were sandboxes made from tractor tires, a swing set, tricycles, and later a mini bike—each kid allowed fifteen minutes before handing it off.

If danger existed, fear didn’t. Kids rode bikes miles to friends’ houses. They played unsupervised. Nobody worried much.

Community, no calendars

The farm sat miles from town, but it wasn’t lonely.

Neighbors and relatives dropped by without calling. Sunday afternoons filled with cards, coffee, cake, sausage, pie, and ice cream.

“We got a lot of company back then,” Bruce says. “More than you see now.”

The phone was a party line—one shared line among multiple households. Calls were limited to ten minutes. Sometimes, you could hear someone on the other end.

“Our neighbor Fred,” Bruce recalls. “You’d hear his heavy breathing. He was an old bachelor. Probably just had nothing to do.”

Windows to a bigger world

If there was time before bed, they might be lucky to watch thirty minutes of black and white television—never before finishing chores. Friends at school talked about Batman or Gilligan’s Island.

“I’d say, ‘Hell no, I didn’t watch it,’” Bruce says. “Couldn’t. We had work to do.”

At first, there were three TV channels, all out of Green Bay. Later, their father installed a rotor on the antenna so they could turn it north and pick up a station from Marquette.

“My God, what an invention,” Bruce says.

They once drove south to visit relatives in Chicago and Milwaukee—the farthest they had ever been from home. The cities felt overwhelming. Concrete everywhere. Apartments stacked on top of each other.

“Might as well have been Mars,” Kathy says.

Bruce agrees. “I couldn’t wait to get back on the farm.”

What else?

College was never discussed. Their parents had eighth grade educations and didn’t know how it worked.

Then one day, Kathy received a postcard from a small college asking about her interests. She checked the box next to “skiing.” She had never been skiing at a resort, but she liked riding an old pair of skis down the hill behind their house.

A recruiter showed up and sat at the kitchen table, chatting with her parents while Kathy took a test in the other room. She was accepted. Tuition was $500 a year.

“I was scared,” Kathy says. She asked Ma if she should go.

“It’s up to you,” Ma bluntly replied.

Kathy went to Suomi College, 120 miles from the farm. There she would meet her future husband and eventually move to Colorado—a place that once seemed impossibly far away.

Just how it was

Looking back now, both describe a life of simplicity—not ease, but clarity.

“We didn’t feel like we were missing anything,” Kathy says. “Because that was all we knew.”

Their childhood unfolded through hard work, necessity, freedom, and community. It’s a way of living that feels hard to imagine now.

Acknowledgments

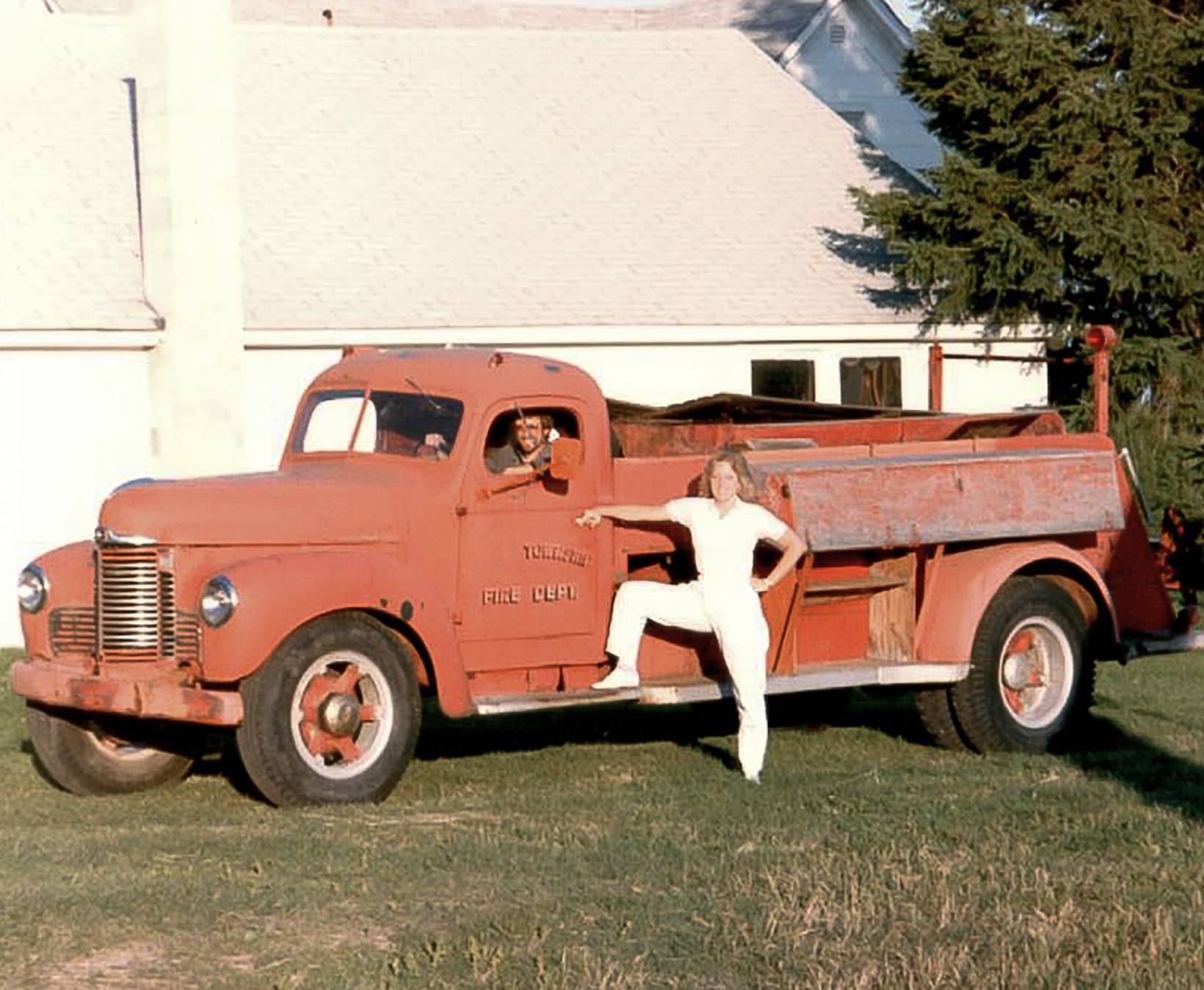

Thank you to Kathy and Bruce for generously sharing their stories and memories. Photographs were diligently compiled by Kay and processed by Barry Van Veen; Barry also took the three photographs from 2016. This piece is dedicated to my late grandfather, Vince Aman.