agentic coding workflows

practices for building with autonomous ai agents

Claude Code is a terminal-native AI coding agent that can execute commands, modify files, and reason over entire codebases autonomously. It’s part of a broader shift toward agentic coding tools—systems that act directly on your repository rather than just suggesting code through a chat interface.

This autonomy creates new leverage—and new failure modes. When used well, it’s like being a staff-level architect with your own team of developers. When used poorly, it generates plausible-but-wrong code at scale. The difference isn’t luck; these tools fail predictably when intent, constraints, and evaluation criteria are underspecified.

The key shift: you’re no longer just writing code. You’re designing interfaces and guardrails for a non-human collaborator with bounded authority.

Below, I share the agentic coding workflow I’ve developed building TB-scale data pipelines and distributed training infrastructure at HOPPR.

For background on Claude Code or installation, see Anthropic’s documentation.

The joy of leverage

One side effect of using Claude Code is that I’m having fun again. I spend more time thinking about what to build and why; less time fighting the mechanics of how. I often feel like a kid hooked on a video game who can’t set it down. When the tedious parts of coding recede, what’s left is the part of engineering that made me enjoy it in the first place.

Workflow

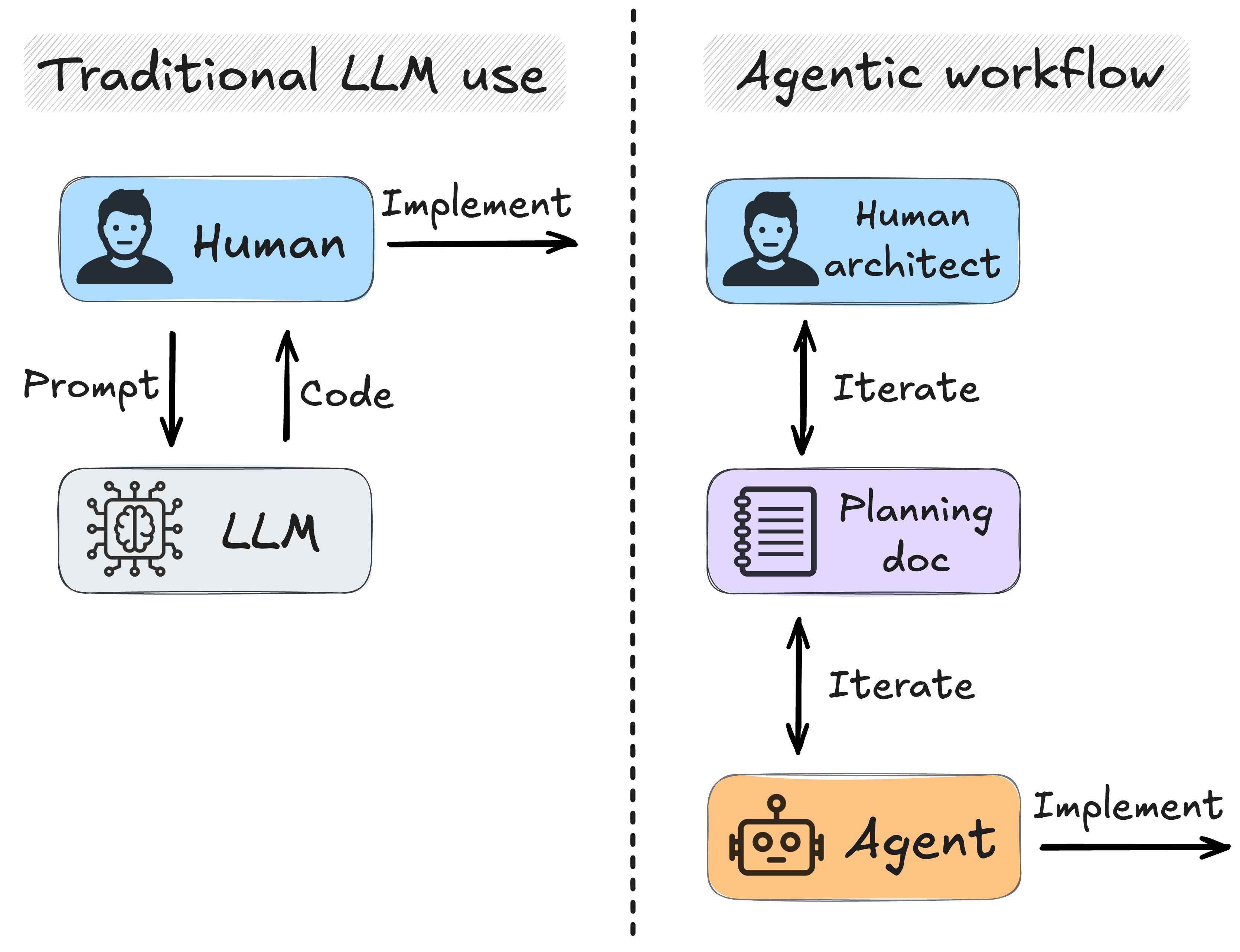

My approach centers on two phases: planning and implementation.

Planning

Every feature—minor or major—begins with a planning document. I act as the architect, describing not just what should be built, but why specific decisions were made. This context helps Claude understand the trade-offs I’m balancing and identify edge cases I might miss.

I think of planning documents as the interface between human and agent. They define intent and constraints in a way the agent can reliably act upon.

Here’s an example of the initial planning document:

### plan_01.md

[preface]

Your task is to...

1. Review the plan below

2. Assess its viability within the existing repository

3. Provide an updated planning document (plan_02.md) for review

[plan]

Note: The “preface” points to my current worktree and claude_ops.md file, both described later in this post.

This kicks off an iterative process. I review Claude’s updated plan, add inline comments, and pass it back. We might create plan_{02, 03, ...}.md until both the approach and implementation details are clear. For complex features, this can take hours—cheaper than debugging a misaligned implementation later.

Before finalizing the plan, I ask Claude: “Are there any points of ambiguity about our plan?” This often surfaces underspecified instructions. It’s easy to assume the agent shares implicit context it doesn’t actually have.

Claude’s execution is impressive, but its real leverage comes from forcing you to externalize architectural intent.

Implementation

After finalizing the plan, I tell Claude Code to implement. With thorough planning, execution tends to be smooth—Claude reads relevant files, writes code, runs tests, and iterates on failures with minimal intervention.

Because the agent acts autonomously, reviewing diffs is critical. Before committing, I inspect changes to ensure they respect my design goals without introducing bloat. Even when requesting concise, reusable code, Claude’s output can drift toward unnecessary abstraction or duplication.

I commit changes frequently. Given how quickly a codebase can evolve during agentic sessions, commits provide clean revert points if the agent diverges.

Note: Execution can take time. To avoid idle waiting, I often run 2–3 tmux sessions with separate Claude Code instances working on orthogonal features.

Best practices

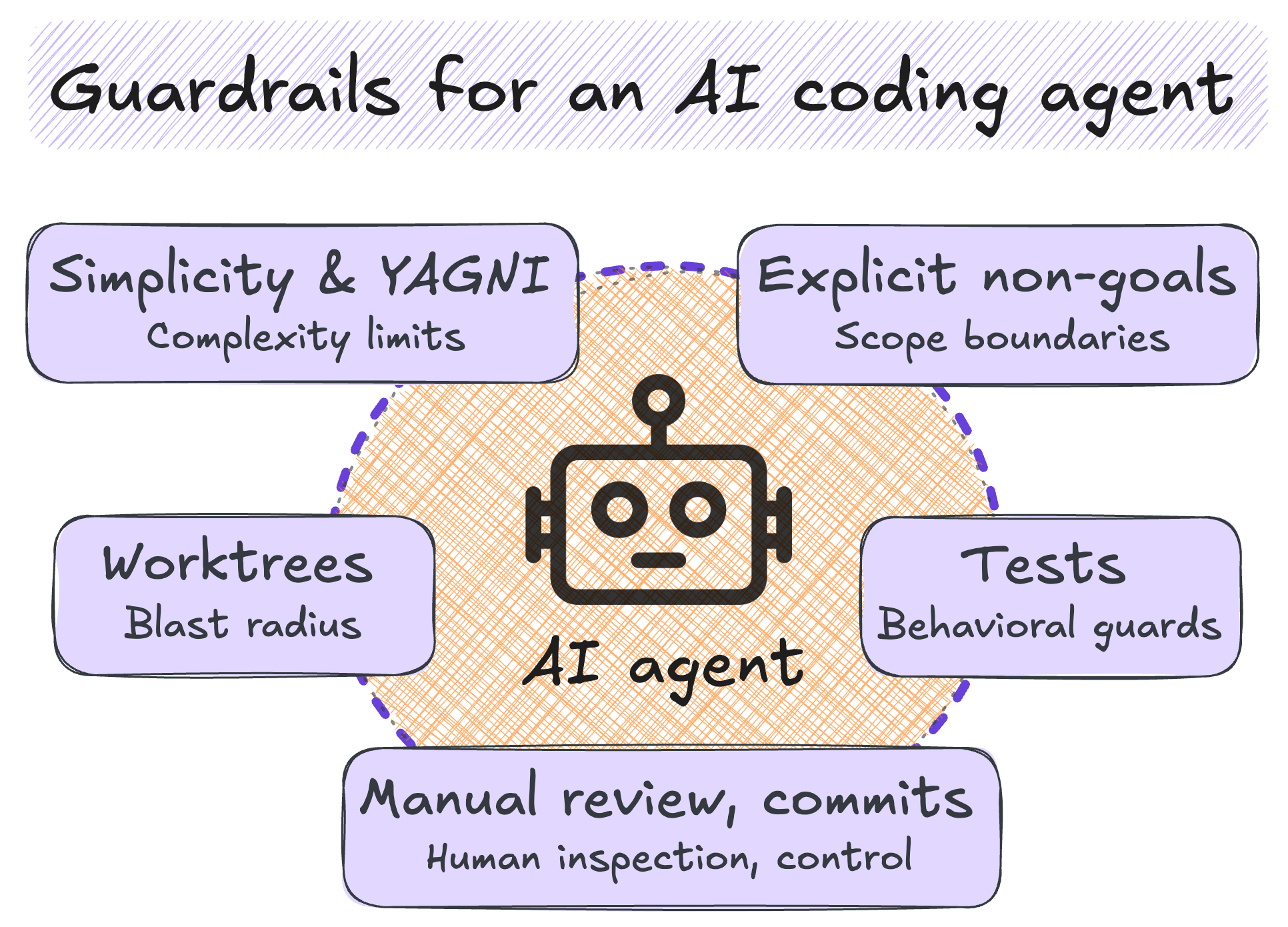

Claude tends to over-engineer unless constrained. To counter this bias, I maintain a claude_ops.md file with coding standards (view the full file here). Below are the high-level principles.

I reference this file in the preface of planning documents: e.g., “First, review /path/to/claude_ops.md to learn our coding standards.”

Test-driven development (TDD)

Write tests first, implement the minimal code to pass, then refactor. With AI agents, tests aren’t just correctness checks—they’re executable specs that constrain agent behavior. They also survive hallucinations and context loss.

Simplicity first

Claude often adds unnecessary abstractions, frameworks, and extensions. Explicitly emphasizing simplicity mitigates complexity drift.

YAGNI (You aren't gonna need it)

Don’t let the agent build for hypothetical futures. Models are trained on codebases full of premature optimization—actively resist this tendency.

Reuse before rewriting

Claude defaults to creating new code rather than adapting existing utilities. Force it to search for reusable components first. This prevents bloat and maintains consistency.

Worktree safety

When an agent can modify many files quickly, blast radius matters. Git worktrees provide containment: Claude can only modify files within the active worktree. I specify this in the preface of my planning docs: e.g., “Your working directory is /path/to/feature/worktree.”).

See this blog for Git worktrees workflows.

Manual commits only

I treat commits as a human-only boundary. Claude proposes changes; I retain authorship over the codebase. A commit is documentation, and I want to own it.

Other tips

Planning is everything

Good planning is the difference between Claude Code accelerating your work and derailing it.

Leverage other LLMs in planning

Input from another LLM can surface edge cases or unnecessary complexity before execution. Tools like Mysti explore structured multi-LLM workflows, though I haven’t used them extensively.

Managing the context window

Claude Code’s context window is large, but manage it deliberately. When switching to a different task, start a fresh session to reset the agent’s working memory.

Not all tasks are created equal

Match workflow rigor to the stakes. Standalone prototypes tolerate loose constraints and fast iteration. Production systems or shared monorepos require thorough planning and review.

Code drift

Claude amplifies existing patterns. Verbose or poorly structured code generates similar output, resulting in wasted context and degraded utility. On larger projects, code quality compounds.

Using --dangerously-skip-permissions

I run Claude Code with this flag (documentation) to avoid constant approvals. The trade-off: active monitoring is key. Without oversight, the agent can pursue wrong approaches or waste time on trivial issues. When this happens, I intervene immediately.

English is the new programming language

Natural language is now executable. Technical fluency amplifies, enabling you to validate output, identify architectural missteps, and intervene before errors compound. Communication and technical skills together make you effective.

Conclusion

These tools are evolving rapidly. Specific tactics may become obsolete, but the intuition for working with autonomous agents—when to trust them, when to override, how to structure work—will remain valuable.

Claude Code shifts the bottleneck from writing code to designing interfaces and constraints for a non-human collaborator. That shift also changes what makes engineering enjoyable: less time fighting mechanics, more time building things that matter.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to colleagues who shaped this thinking: John Paulett, John Gillotte, Robert Bakos, Khan Siddiqui, Eric Brattain, Woojin Kim, and Kyong Song.

Resources

Additional resources I’ve found useful:

- Claude Code best practices from Anthropic.

- Blog post on using Claude Code features.

- Blog post on writing a good

CLAUDE.mdfile. - HappyApp: macOS app pairing Claude Code with a polished UI and session management. Useful for long workflows or checking progress on the go.